The Escalating Accountability Mandate…

Measurability and accountability—it’s one thing to feel the heat, it’s another to get burned. To understand why so many marketers are relying on a new and evolving array of automation tools, let’s consider one fact: Today, one of the key drivers of B2B demand generation is proving the value of marketing investments. What are you getting for your marketing dollars? And how do you quantify it?

As revenue marketing executives seek to answer these questions, they’re more focused than ever on measurement, accountability and increasing performance across programs, marketing activities and media. In fact, according to recent marketing outlook reports by the CMO Council, marketers are under “increased pressure to improve relevance, accountability and performance of their organizations.”

In other words, marketers are being told to deliver the goods. Those who succeed are rewarded. Those who do not are at risk. (The average employment span for a CMO at any one company—approximately 2 years.).

Hence, the increased reliance on—and investments in—marketing automation an ABM solutions to help measure results and manage programs. The universal goals, it seems, are to improve and quantify the efficiency and effectiveness of marketing initiatives, and significantly improve the allocation and return on marketing spend. Or, put in its simplest and most personal terms—you need to enhance performance to create a sustainable, competitive advantage in today’s marketplace.

The question is: How do you do it? Or, more specifically, how do you plan,execute and measure a highly-calibrated demand generation strategy that takes into account your target audience, solution set, price point, market conditions, competitive environment and current initiatives?

To answer these questions (I’ll put a stake in the ground in a moment), it’s first necessary to make a few assumptions. First, I’m assuming that as you read this, you already understand the need to align Sales and Marketing more closely than ever to better support the sales process and drive demand. I’m assuming that you’ve embraced new social media tools and marketing automation technologies, that you have the dashboards in place to measure results, and that you genuinely desire to increase performance. And if not, your career is likely facing an extinction-level event!

Additionally, I believe that I do not need to delve into areas that are best left to specialists — including Revenue Architects — such as the mechanics of digital marketing, search and social media marketing and sales, the operation of marketing automation, deploying effective ABM programs, formatting landing pages for maximum conversion, and the criteria and process for lead scoring and distribution.

Today’s universal mission and objectives. Marketers, of their initiatives. Marketing’s attribution to revenue is critical. Those who do are today’s true “revenue marketers”. The others…well they may be looking for new jobs soon.

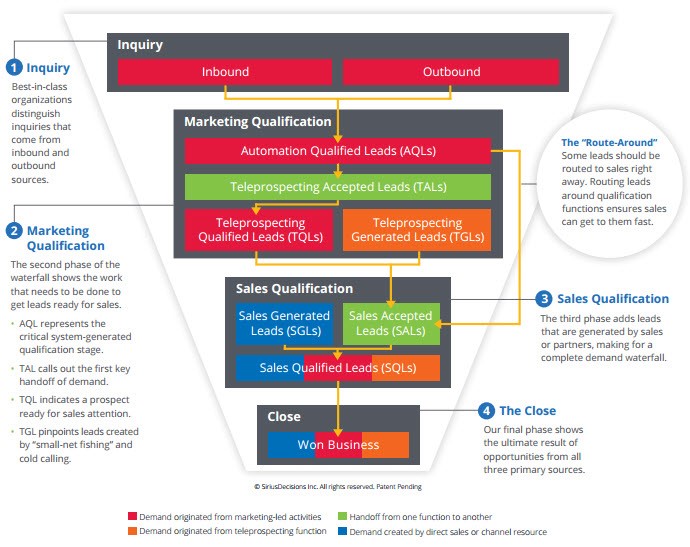

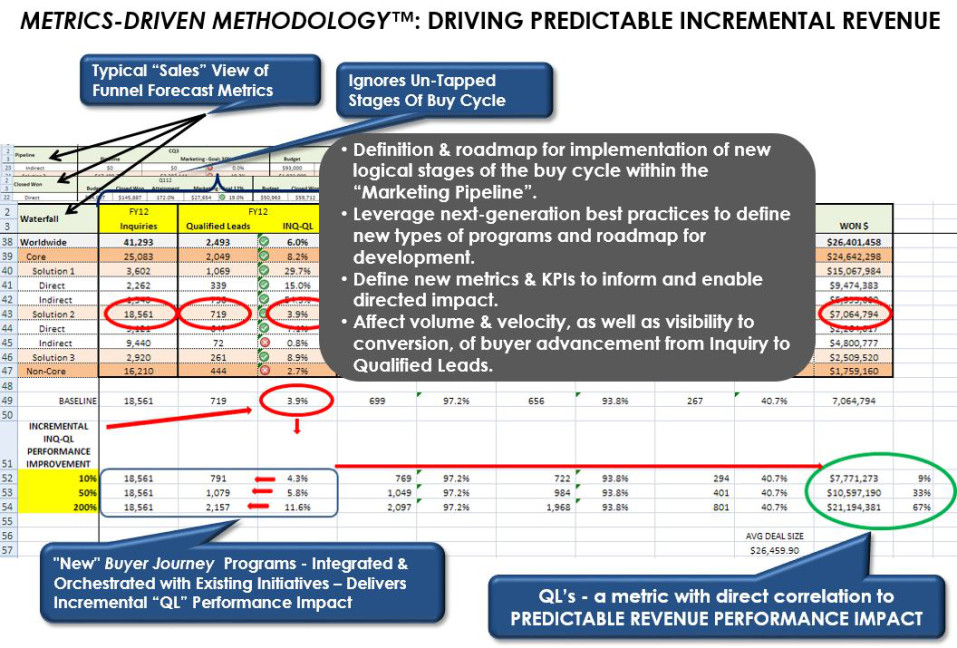

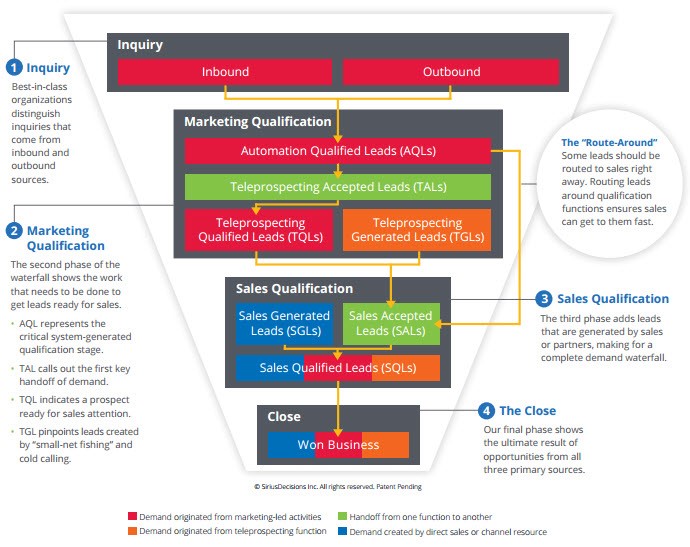

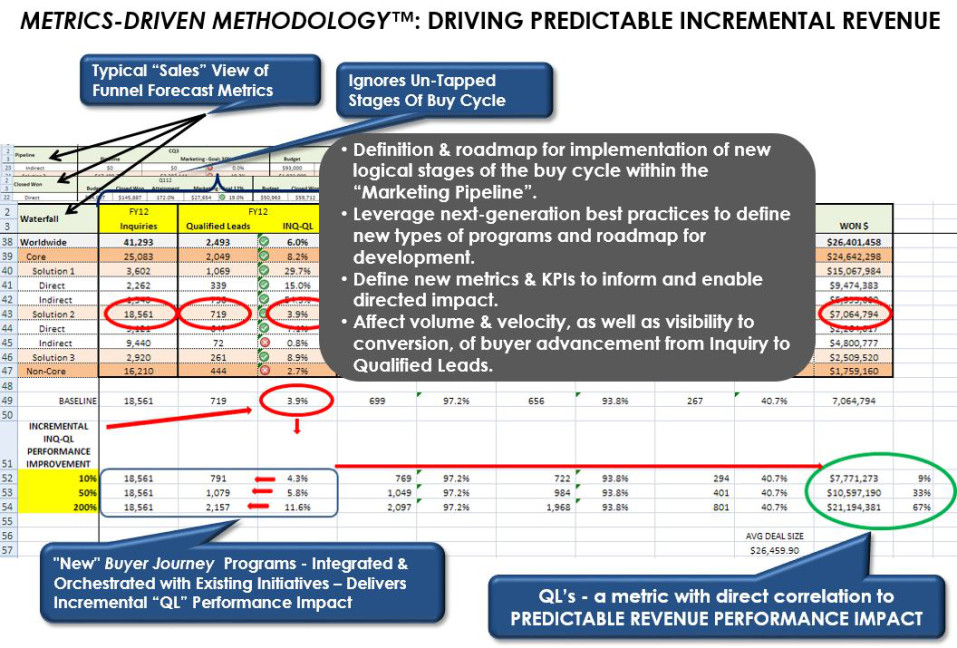

Below you’ll find SiriusDecisions Demand Waterfall. You’ll also find a more detailed view of how best-in-class companies are measuring and analyzing key levers that increase Marketing’s contribution to revenue performance, including conversion in the pipeline via a Metrics-Driven Methodology™…

But enough of the qualifiers. To the heart of the matter. To improve marketing performance and create a sustainable, competitive advantage, you need to do more than rely on new technologies and digital media as ends unto themselves. Rather, you need to return to the foundational principles of solid, effective demand generation—and base your programs on learnings and insights that have proven themselves on countless occasions in the marketplace – ultimately in the context of a well-defined buyer engagement strategy. Yes, new technologies and digital media are remarkable—awe-inspiring in fact—but you need to balance your use of them (and your thinking about how to fully maximize their potential) with several core principles that are often overlooked.

One final thought before we proceed: Let’s define Demand Generation and Revenue Marketing. Before launching into the foundational elements, there’s one point of order. Let’s define demand generation as results-based marketing that supports Sales, and ultimately revenue delivery. Demand generation serves the purpose of generating, nurturing and converting leads into qualified sales opportunities. When effective, it makes both selling and buying a more comfortable and efficient process. And when compared to other forms of marketing, it is by far the most measurable and therefore accountable side of the business.

The challenge is that until recent years, demand generation meant “lead generation” and was associated too often with one-off marketing campaigns, often supported by telesales, less sophisticated landing and registration pages, static banner ads and e-mail blasts. And to compound things, marketing automation platforms were basically used as “spam cannons”. Ultimately, it was measured by short-term results and myopic questions such as “How many leads did the program produce?”

However, the fact is in complex B2B sales, demand generation isn’t about instant gratification, but rather buyer engagement which requires a sustained effort, often over a relatively long period of time.

Is your career facing an extinction-level event?