The Numbers Behind the Mustard Wars

Ketchup wars! Mustard wars! It’s a Condiment Armageddon! And it’s also an analytical opportunity.

This spring, Heinz relaunched its mustard with a new, improved formulation to compete head-to-head with French’s, the category leader. Answering this shot across the bow, French’s launched a new ketchup, challenging Heinz’s leadership. At least two publications have called this situation a “war” — presumably between a pair of rival condiment nations.

Over the last 12 months, Heinz’s mustard’s $10 million in sales represents a 300 percent year-over-year increase, while French’s new-to-the-market ketchup grabbed about $3 million. Looking at each brand’s mainstay product, Heinz’s ketchup is up three percent, while French’s mustard is down 3.9 percent. That might point to a clear winner and loser in the great condiment skirmish of 2015, but I think broader trends say they both may end up being losers.

In recent months, Fortune (“The War on Big Food”) and The New York Times (“Small Food Brands, Big Successes”) have pointed to the proliferation of small brands. Boston Consulting Group analyzed this shift, showing that large food companies lost 2.3 share points to smaller ones from 2009 to 2013 and another 0.7 points in 2014.

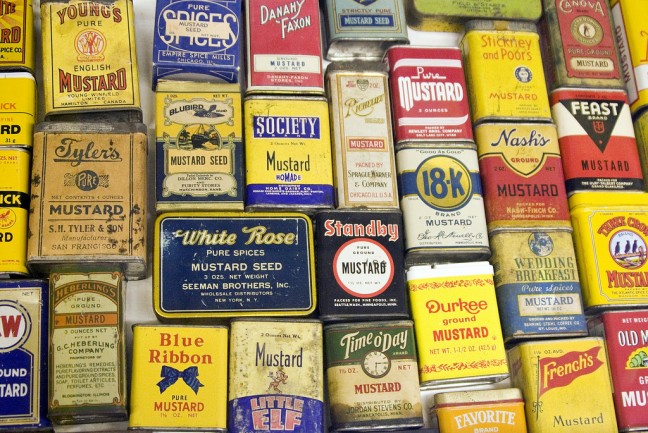

So how do we account for entrepreneurial brands in all of this? Well, hiding in the data, there’s the ascendancy of “all other.” And that’s a group that entrepreneurs know well. After analyzing the top brands in a category, there’s always dozens of others that make up the long tail of results — usually ranging from a few percent to maybe 20 percent of the category’s sales. In my analysis, there’s never enough space to list them all out, so they get collapsed into an “all other” grouping. But that’s where the momentum and innovation often resides, waiting to break out.

In condiments, there’s share dominance by the big guys. The top three brands in ketchup make up 97 percent of sales, and the top six brands in mustard make up 83 percent. Aside from those, no other brand represents more than two percent of sales in ketchup and mustard.

But Ketchup grew $21.1 million (+2.6 percent) this year. We can attribute 74 percent of that growth to Heinz, 15 percent to French’s, 9 percent to private label, and 6 percent to all other brands. (This doesn’t add to 100 percent because of two medium-sized brands that declined.)

In mustard, it’s even more striking. The category grew $2.0 million (up 0.5 percent). Many brands declined, and others grew at rapid rates. Gainers picked up $10.8 million, and declining brands lost $8.9 million. French’s was one of the notable decliners, dragging down the entire category. Meanwhile, Heinz’s gain was 3.85 times of the category’s growth, and the “all other” segment added 1.37 times more than the category’s growth, drawing from brands like Inglehoffer, Maille, Boar’s Head, and Annie’s Naturals, one of those entrepreneurial brands that is starting to see significant scale.

Even more telling is that this data set also doesn’t account for the natural and specialty channel, which has an even greater assortment of small brands (such as Tessemae’s and Sir Kensington’s) — and I suspect, even for the graying condiment category, some trends are starting in that channel and migrating to conventional grocery outlets. My local Shaw’s and Star Market stores have been increasing assortment of specialty products, and Target has an initiative to do the same, both in terms of bringing on new brands and co-developing sets with emerging product partners. (Hey, I loved finding Intelligentsia Coffee at my local Target last week!) In these cases, there is no doubt smaller brands are stealing shelf space — which is eventually going to translate into share.

I often hear from folks in the food industry who have an idea to make something better. These have included colleagues who wanted to improve baby and toddler nutrition, make tasty yogurt with better health attributes, bring Asian snacks to an American audience, and more. Most of them are still in business and thriving. And while they (mostly) aren’t becoming big businesses, they are providing livelihoods for their owners and employees. Some have broken out; more will.

Consumers — particularly Millennials — are reacting to this demonstration of authenticity and are enjoying the newfound availability of novel products on shelves where they shop. And they pay premium prices for this benefit. In some cases, the premium isn’t much in dollars and cents, and consumers are willing to make the trade.

In other cases, larger premiums simply mean that new-age products are treats or consumers set aside larger budgets for packaged food than older generations have. But in all cases, it’s leading to category growth at the expense of entrenched brands.

Among the headlines of wars among the big players in the food business, be sure to look for the hidden story of what’s happening with smaller brands. If recent history is any lesson, there are some great stories that are waiting to spread.

Reposted from Project NOSH. Thanks to Jeff Klineman for his editing and for allowing re-use.