Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/inggroup/25397449183

We were meeting in our wood-paneled boardroom. I was part of a broker team hosting business planning sessions between a major Northeastern supermarket and a few dozen of our CPG manufacturer clients.

During one session, a large beverage manufacturer suddenly announced that they were going to drastically cut the depth and breadth of their discounts. To put it mildly, this announcement went over like a bomb. There may have been some screaming and cursing.

It seems this manufacturer had a bad year, and so management wanted to cut back on discounting in order to boost margins.

Unfortunately, they had missed some important points.

They were focusing entirely on their internal financials. They did not consider the supermarket’s goals, one of which was growing their share of the manufacturers’ discount spending, also known as trade spending. There might have been an opportunity to work together on mutual goals. And most seriously, they did not consider the consumers’ perspective.

For most of my clients, discounting is used to improve volume, and plans rarely change from year to year. It is a brute-force tool.

Compared to those clients, this beverage supplier had the right idea. But though it’s tempting to use price cuts to improve volume, it can leave money behind if the market is willing to pay higher prices. This supplier simply wanted to reduce their discounting — a worthy enough goal, perhaps, but without the right tools to present their case. And with the right support, they might have been prevented an important customer from screaming at them.

When I work with clients in similar situations, I use a range of specialized tools to help them understand their consumers’ willingness to pay for their products. Here are the three tools I use most often:

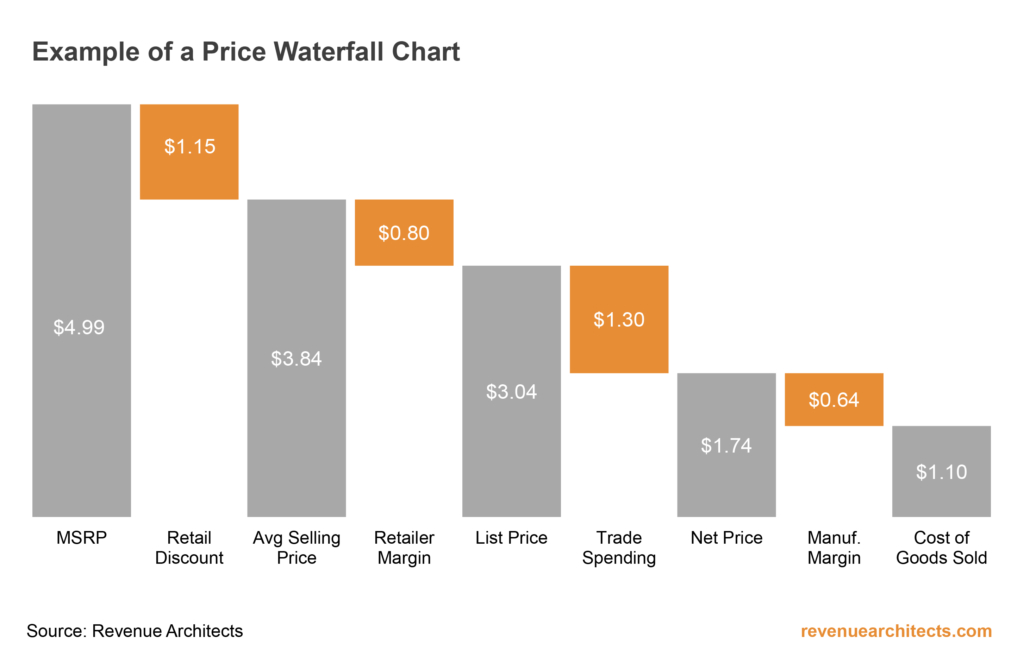

1. Price waterfall: assesses the current situation and whether there is any leakage. What margins are earned at various points in the value chain, and how much of a role does discounting play?

When I conducted this analysis for one manufacturer, it was shockingly clear their internal margins were almost non-existent after accounting for all of their trade expenses. Trade spending was crowding out nearly all opportunity to earn a profit.

In other versions of this chart, additional expenses like allowances for spoils, cash payment terms, and others can be included to provide a more comprehensive view.

The price waterfall chart served as a useful internal communication tool to visually demonstrate where margin might be leaking.

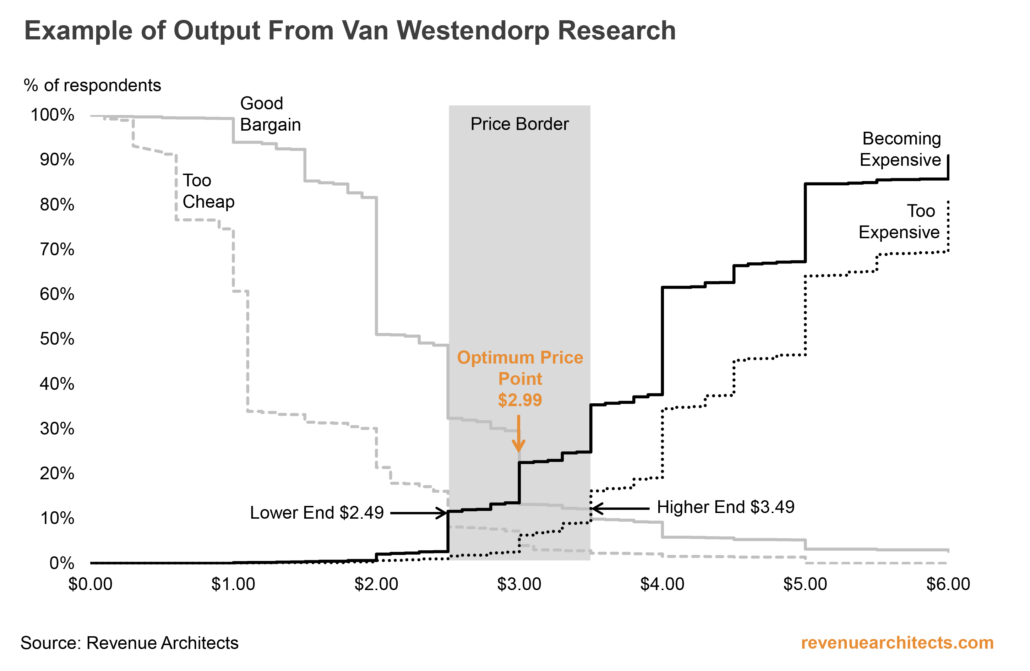

2. Van Westendorp: assesses consumers’ willingness-to-pay. What is the range of acceptable prices? What are the minimum and maximum acceptable prices?

One of my clients typically discounted from $2.99 to $2.19 or $2.29. Many of their retailers demanded a minimum 20 to 25 percent discount, which is why those price points were selected. But we found that consumers were just as willing to pay $2.49 on sale, and one field experiment actually showed higher volumes at $2.49 than $2.29. The retailer made an exception to allow a lower discount on promotion, and everyone earned more dollar margin and we demonstrated that volume could actually grow.

In other words, I helped my client develop a comprehensive selling story that made for an appealing scenario that resulted in a reasonable request to their trading partners.

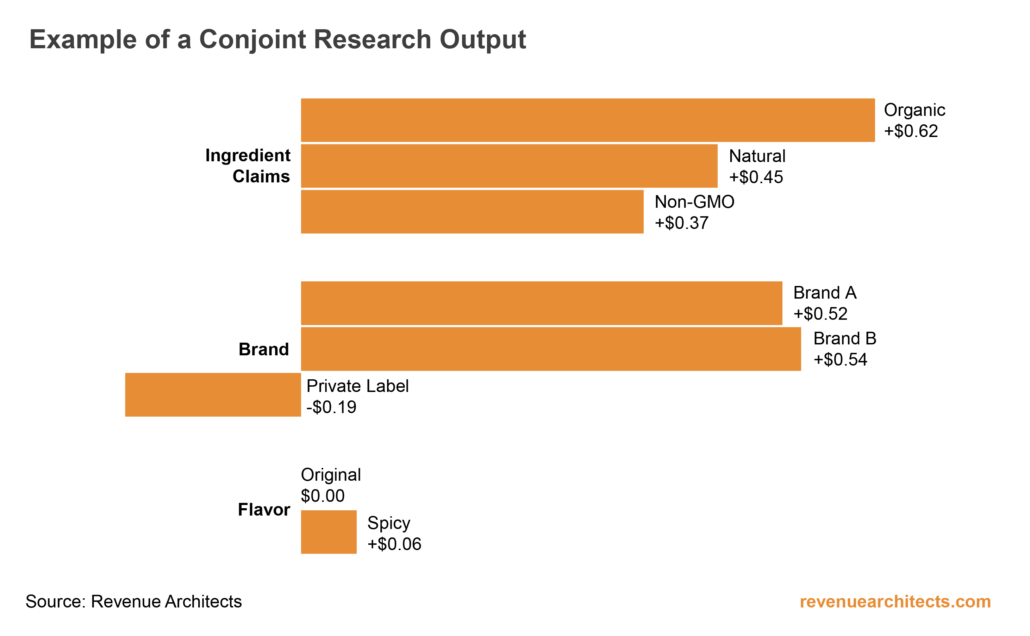

3. Conjoint: evaluates various product attributes: How much do consumers value different product attributes, and how does that translate into the price they are willing to pay?

By using this complex research technique, we can learn how consumers assign value to various attributes. This chart is a small snapshot of the output available from conjoint research. Ultimately, this research can result in a model that allows you to mix-and-match product attributes to create complete product concepts, balanced by different price levels, that allows you to see the impact on consumer preference and willingness-to-pay.

One of my clients used this technique to redesign their entire product line, resulting in a new lineup of product sizes, product contents, and — of course — evidence-based price levels that could be defended in a meeting with their retail buyers.

* * *

At the end of the day, discounting is just one tool in your pricing toolbox. There are plenty of others you can add to the collection.

It’s easy, even tempting, to rely on discounting, as it can have an immediate impact on volume. But there’s the danger of leaving money on the table and training your consumers to buy at lower prices. No one ever wins when prices spiral to the bottom. Instead, you need to equip yourself with accurate, compelling, consumer-driven information to ensure you earn the price you deserve.